Robert Mitchum in Undercurrent (Vincente Minnelli, 1946) – detail from the festival’s poster. festival.ilcinemaritrovato.it

Il Cinema Ritrovato is a festival in constant expansion: since I first attended it in 2003, it has grown bigger and bigger, acquiring new screens and theatres, and the amount of films presented has long ceased to be within the scale of what a single human being can watch in a week. This year the titles were about 500, of which I managed to see a respectable 10%: the sheer bulk of the offer forces you to carve your own paths across sections and retrospectives, and compiling your day’s schedule is always exciting: pen and highlighter are your best friends when consulting the catalogue – a gorgeous publication about the size of a phone book – to pick out the screenings you can’t miss, and those you will be able not to miss.

I chose to only go see movies I hadn’t seen before: a decision that can be heartbreaking, for example when it means skipping the whole retrospective on Robert Mitchum, or the chance to see All That Heaven Allows and Mildred Pierce on the magnificent screen of the Cinema Arlecchino.

It also meant missing out on the first great event in Piazza Maggiore, the projection of the restoration of Jean Vigo’s L’Atalante (a film that means a lot to Italian cinephiles) and going to see Max Ophüls’ little-known Divine, from 1934, instead. Set in the decadent world of Paris nightclubs, and surprisingly explicit in the representation of drug use, prostitution and bisexuality, this lovely film bears the mark of screenwriter Colette, whose relation with the moving pictures was explored in a retrospective that also included the gender-bending Lac aux dames (Marc Allégret, 1934) and the unforgettable lesbian romance Mädchen in Uniform (Leontine Sagan, 1931).

In the mornings, I attended the screenings at the Cinema Jolly, devoted to two film series: a follow-up to last year’s Universal Pictures retrospective, and one about American director William K. Howard. This meant spending every morning in Hollywood, in the early thirties: outlandish outfits and deco interiors, witty dialogues and mysterious ladies. A description that fits works as different as Lois Weber’s Sensation Seekers (1927), a moralizing silent drama – basically a long Christian sermon, enjoyable only because of the beautiful Billie Dove – and Tod Browning’s Outside the Law, a story of kind-hearted gangsters who strive to save a policeman’s life because he is the father of a child they are fond of; but especially the elegant By Candlelight (James Whale, 1933), a comedy of errors that brings class relationship into play when a girl mistakes a butler for a prince, and Ladies Must Love (E. A. Dupont, 1933), typical Pre-Code Hollywood, where a group of women, smartly dressed but late with the rent, sign an agreement to share any gifts they shall receive from wealthy men. And if William K. Howard is known today mainly as director of The Power and the Glory (1933) – where the life of a man is reconstructed in a series of flashbacks, a narrative structure that influenced Citizen Kane – we learned that he had already attempted something similar in The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932), a fast-paced courtroom drama with Joan Bennett and complex leaps back and forth in time, and that he was also the author of charming romantic comedies like Don’t Bet on Women (1931) and of a stylized drama like Transatlantic (1931), where the inventive direction matches the suggestive lighting of the cinematography by the great James Wong Howe.

Lobby card for The Power and the Glory (William K. Howard, 1933). doctormacro.com

The “100 Years Ago” retrospective brought us back to 1917, first in ancient Roman costumes for Ugo Falena’s Caligula – a beautifully tinted, big Italian spectacle with suggestive location shots of Roman ruins – and then to Poland for the first feature film produced in the country, which is also the oldest surviving performance by Pola Negri: Bestia, redistributed in the US as The Polish Dancer in 1922, marked the beginning of her international stardom and in it she already displays the wild temperament that would be the mark of her screen persona.

Yet the silent film I was looking forward most to was a funny little German film from 1929, Ich küsse Ihre Hand, Madame, which is mainly of interest due to the presence of Marlene Dietrich in one of her few silent, pre-Blue Angel film appearances: her image is undeveloped but already there, and if it’s hard for us now not to project the shadow of what was to come on this larval stage, still it would be impossible, from this film alone, to imagine the mythological proportions her legend was to achieve in Hollywood with Josef von Sternberg.

Another film by the same author, obscure Czech-Austrian director Robert Land, was shown in an evening screening with a carbon-arc projector: Die Kleine Veronika, a 1930 classic of the Austrian silent age. Notable for the beautiful photography in exterior shots and as a document of pre-war Vienna, this film is easy to love for the truthful simplicity of the acting, the matter-of-fact attitude towards the world of prostitution and the sensibility with which the main character is portrayed: a reminder of how different the representation of sexual taboos (and of the consequences of their infringement) could be between European cinema and Hollywood. Besides the quality of the film itself, a projection with the carbon-arc lamp is always an enchanting experience – though in this case the live soundtrack was a drawback for me: very beautiful in itself, the music didn’t match the pace of the action and thus had a distracting effect, a major issue when accompanying silent films.

The very opposite goes for the new musical score accompanying the restoration of the British silent film The Informer (Arthur Robison, 1929): inventive and enthralling, it’s a soundtrack that drags you into the world of the film, the Irish underworld, and into a story of love and betrayal, with an outstanding cinematography that prefigures the noirs of the 40s and a suggestive, atmospheric lavender tint that gives the images a sense of perpetual dusk.

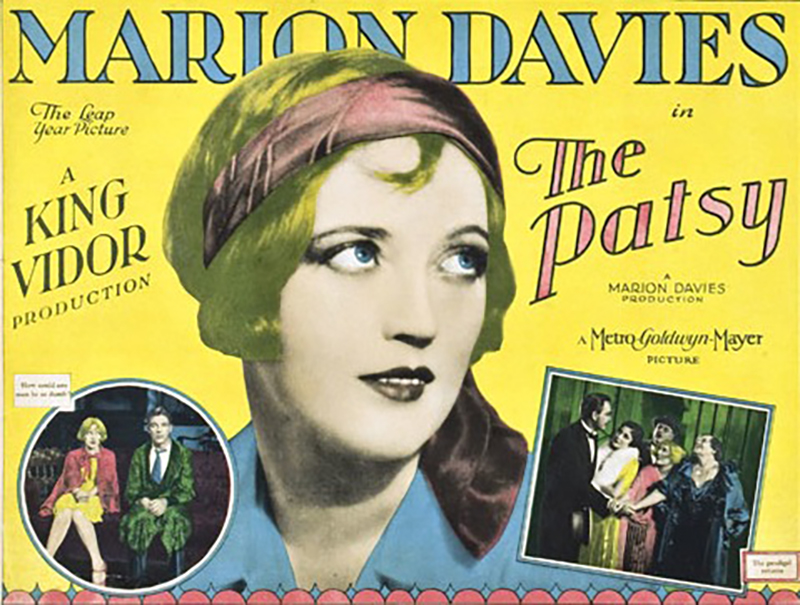

A silent film was also my only exception to the never-before-seen-only rule: because King Vidor’s The Patsy on the screen of Piazza Maggiore is not the kind of projection you stumble upon every day. This irresistible comedy is one the director’s finest, clearest works, and a peak of the stylistic perfection attained by cinema in the late twenties: Marion Davies, one of the most underrated stars of the silent era, shines throughout the film with her incredible talent and outstanding beauty that can still win any audience more than 80 years later.

Lobby Card for The Patsy (King Vidor, 1928). Wikipedia

The single personality that dominated this edition was definitely German film director Helmut Käutner, whose work was presented through a selection of nine films, in chronological order – the best way to follow an author who started as a nonconformist filmmaker under the Nazi regime to become a major name in the post-war years and end up being considered a dinosaur by the younger generation of the New German Cinema. I was already familiar with some of his most famous titles, like Auf Wiedersehen, Franziska! (1941) and Der Hauptmann von Köpenick (1955), but had no idea his work was so diverse. Große Freiheit Nr. 7, the story of an unlucky sailor turned entertainer, with Hans Albers as the protagonist, was shot in 1944 but banned by the authorities as too depressing and anti-heroic: the exact reasons that make it noteworthy today, together with the Agfacolor photography that prefigure the warm, brown tones of Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980).

The peak of the retrospective – and one of the peaks of the festival – came with Unter den Brücken (1944), a moving, deeply human love story set on a barge on the Spree. This unforgettable film is a sort of German twin of L’Atalante, but with a fascinating power all of its own. Above all: the scene where Carl Raddatz explains the noises of the boat to the worried girl (and making Carl Raddatz, the ugliest leading man to ever cross the screen, look almost attractive, which is a miracle not even a masterpiece like Veit Harlan’s Opfergang was able to achieve). Although shot in Berlin during the height of the allied bombings, the film shows no trace of contemporary events, setting itself apart from time and contingencies, and outside the cinematographic standards of Nazi ideology.

And if under the Nazi regime not being political was a very political choice, in the reconstruction years Käutner didn’t avoid raising controversial themes either, such as the fate of arms dealers and speculators in the post-war years in Epilog – Das Geheimnis der Orplid (1950), a tense thriller with a striking closing sequence, and the social problems caused by the division of Germany in Himmel ohne Sterne (1955). On a lighter note, Ludwig II. – Glanz und Ende eines Königs (1955) has spectacular colours and costumes, but is surpassed in visual opulence by Das Glas Wasser (1960), a delightful musical comedy set in 18th-century England, with songs by Käutner himself, and the great Gustaf Gründgens – the boss of the gangsters in Fritz Lang’s M – in his last film appearance.

Helmut Käutner credited as director in the opening titles from Romanze in Moll (1943). archive.org

I have a soft spot for Mexican cinema of the Golden Age, a passion that was born at the festival, years ago, when I saw Emilio Fernández’s Enamorada (1946): from then on I tried to watch as much as I could of this bizarre cinematography, rich in brilliant directors – whose names are obliterated in the public consciousness by the shadow of Luis Buñuel – and a pantheon of stars easy to get attached to. A retrospective at the Zeughauskino in Berlin earlier this year showed masterpieces like Julio Bracho’s Distinto amanecer and Fernández’s Salón México in wonderful restored copies, so I couldn’t miss the festival’s Revolution and Adventure section that focused on the social changes brought on by the Revolution as reflected on the Mexican screen over three decades (1930-1960).

Openly political was the first film presented, El compadre Mendoza (1933), the second part of a trilogy by Fernando de Fuentes, which is considered a milestone in the country’s cinematography and casts a critical look at the Revolution and its consequences for people: the story of a rich landowner who tries hypocritically to ingratiate himself with both parties, but finds himself in a difficult position when he has to choose, and convenience clashes with ethics.

Dos monjes (1934) by Juan Bustillo Oro, on the other hand, is a fantastic story of love and revenge, where two friends who fought over the same woman find themselves together in a monastery – an interesting example of “Mexican Gothic”, the film bears the influence of German expressionism – Schatten (1923) in particular, in the costumes and set designs, exploding in the final sequence with a gathering of scary masks: loved by André Breton, this curious film is unlike any other I’ve seen from the same period.

Una familia de tantas (1948) by Alejandro Galindo is a comedy of manners that dramatizes the challenges Mexican society had to face with the advent of modernisation, here represented by a vacuum cleaner: the modern appliance introduced into a common family against the resistance of the old-fashioned father is a first step towards the loosening of the strict traditional social roles – this entertaining little film is especially interesting to the Italian viewer as it parallels in style and themes many examples of our national cinema from back then.

And if the classic Historia de un gran amor (1942), by Julio Bracho, was for me kind of a disappointment for its excessive length and verbosity, it still displays all the typical traits of the flamboyant melodramas that made Mexican cinema so outstanding: class conflict, forbidden love and violent revenge. Roberto Gavaldón’s El rebozo de Soledad (1952) stars Arturo de Córdova as an idealistic doctor who chooses to stay in the country to help the poor instead of moving to the big city to pursue his career among the corrupted, and though the rhetorical tones of the second part sound too preachy to be realistic (besides some doubtful choices in gender politics) it is well worth seeing as a depiction of the contradictions that were still dividing the country.

Faithful to my first love Emilio Fernández, I was eager to see Maclovia (1948) and wasn’t let down: María Félix and Pedro Armendáriz in the cast are always a guarantee of quality, and the beautiful photography by Gabriel Figueroa highlights the fascinating landscapes. The shots of the boats, with their fishing nets, on the lake at sunset leave a dreamy aftertaste in one’s memory, and the feeling of actually having been to Mexico, sometime in the past. The story of the impeded love between the poorest fisherman and the most beautiful girl of the village assumes larger-than-life proportions, with the characters and their feelings surging to the magniloquence of Greek tragedy. Because that’s what we want from Mexican melodramas: the epic of romance, fight against oppression, and over-the-top passions that flood people’s lives. In this sense, the height of the section was also one of the strangest films of the festival, the unforgettable Aventurera (Alberto Gout, 1950): recounting the plot would be not only pointless but impossible, as there are twists every five minutes, making it one of the fastest, most compressed series of events I’ve ever seen. Renowned as the peak of the Rumberas film genre, it stars Ninón Sevilla – who also choreographed the very camp musical numbers reminiscent of Busby Berkeley and Carmen Miranda – as the toughest, most aggressive dark lady of all time, against a cast that also features Miguel Inclán in a sinister, mute part and Andrea Palma as the wicked mother in law/brothel madam: this delirious film, in equal parts noir, melodrama and musical, defies all plausibility – even demanding the gift of ubiquity for the plot to work – in the name of sentimental grandeur. It is easier to call it a masterpiece than to call it a good film: one of the visual experiences that alone would be worth the plane ticket to the festival.

Jorge Mondragón and Ninón Sevilla in Aventurera (Alberto Gout, 1950). youtube.com

But, once more, it’s not the films alone, it’s the context that makes Il Cinema Ritrovato a unique experience: paradigmatic in this sense was the screening, in Piazza Maggiore, of a famous but rare, almost invisible, Italian film: Marco Ferreri’s Break Up (L’uomo dei cinque palloni, 1967). An allegoric tale of a man who goes insane in an effort to measure exactly how much air fits in a balloon – played by the insuperable Mastroianni in one of his most understated performances –, this complex yet crystal clear film is at the same time metaphysical and hilarious, and opens itself up to a variety of interpretations, from sarcastic reflection on the rise of industrialisation to apologue on the conflict between rationality and irrationality, to an analysis of the cultural climate of the 1960s and much more. Part black-and-white, part colour, the film explodes in the nightclub sequence, when the screen is filled with red, white and blue balloons: and the Cineteca had a great idea in putting one such balloon on every seat before the projection. Soon the whole square was engulfed with them – and popping balloons after the screening became a spontaneous, collective happening perfectly in line with the spirit of the film.

I can’t imagine anything like this happening anywhere else: next year I’ll do it again.